This is a bit of follow-up to your questions, since they are excellent and relevant questions, hence providing more information will be helpful . . .

ConnieR wrote:Hi,

I'm mostly a classical music composer, but I would like to do what I would call "cross-over" music, like music with a country feel, or rock, etc. Sort of like film scores, which combine orchestral and other styles of music, or the instrumental arrangements on some of the country singers' Christmas CD's. My question is this, is Notion suitable for that, or should I look for something different?

As noted in my first reply, NOTION is excellent for these composing activities, especially if one of your goals is to create songs that you can sell on CD or for purposes of marketing your songs to musical groups, directors, and so forth . . .

If the only interest is in composing, per se, then I suppose a pencil and some blank sheet music will work nicely, but with NOTION you get to hear the instruments, which especially for "play by ear" musicians who are venturing into composing in more genres is very important . . .

And for reference, I interpret "I'm mostly a classical music composer" as indicating that you are reasonably proficient with music notation, which is important, since NOTION is a music notation composing program, although if you play a MIDI instrument (keyboard, electric guitar, or electric bass), then you can input music by playing it on a MIDI instrument . . .

On the other hand, if you are new to music notation, then it just takes a bit more work, since you can teach yourself enough music notation to be productive in NOTION, where as an example of a simplified system for doing music notation, I only learned soprano treble clef as a child singing in a liturgical boys choir, so I am reasonably proficient in soprano treble clef but generally have no clue about the other clefs other than that they are weird and either map to entirely different notes than the soprano treble clef or are sufficiently offset to require me (a) to remember offset, (b) to do a real-time mental mapping based on the offset, and (c) to do all (a) and (b) sufficiently fast to make everything happen in a timely way, which is not something I can do at present, hence I avoid it diligently . . .

The strategy I use is based on logic, mathematics, and facts, where there are two very important facts:

(1) There are only 12 notes (C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B) . . .

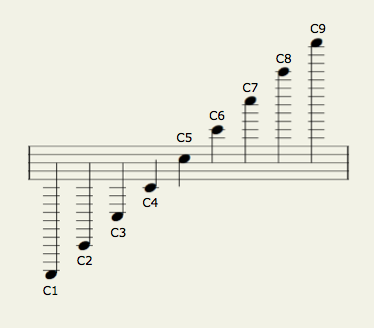

(2) There are 8 or so octaves, where if you include the subsonic frequencies and some of the nearly supersonic frequencies, there are 10 octaves, more or less, but nearly nobody can hear the lowest octave and the highest two octaves, hence at least for what one might call "popular music" they essentially are irrelevant . . .

[

NOTE: I can hear some of the subsonic notes, but I think that the practical upper limit of my hearing is around 13.5-kHz, and notes in that range are so high that nobody can make sense of them, even though the formally defined "full range of normal human hearing" is 20-Hz to 20,000-Hz . . . ]

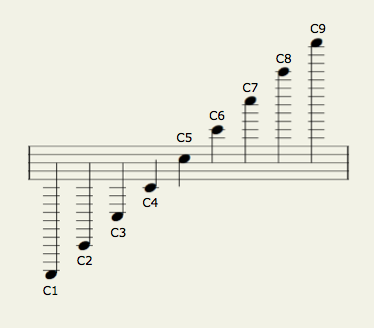

Using scientific pitch notation, (a) the lowest notes are the ones in the C0 octave, where C0 is 16.352-Hz and is subsonic, which for most people indicates that you can feel the sound but cannot actually hear it and (b) the highest notes are the ones in the C10 octave, where C10 is 16744.0 and the highest note in the C10 octave is B10, which is 31608.5-Hz and for the most part is nearly absurdly higher than the highest note in the normal range of human hearing . . .

[

NOTE: C10 is not shown in the following chart, which is a clue how nearly absurdly high it is . . . ]

[SOURCE:

Scientific Pitch Notation (wikipedia) ]

This is a mapping of the keys on an 88-key piano to the corresponding scientific pitch notation octaves, where the highest notes at the far-right have fundamental frequencies in 3,000-Hz to 4,200-Hz range, although there are higher frequency harmonics and overtones . . .

[SOURCE:

Piano Key Frequencies (wikipedia) ]

With this information in mind, the practical reality is that by focusing on soprano treble clef, which includes a few notes below the staff and a few notes above the staff, this provides a range of approximately three octaves, as shown in the following diagram . . .

[

NOTE: It is not so difficult to remember C3 through C7, which is four octaves and is plenty of notes . . . ]

C1 to C9 on the Soprano Treble Clef

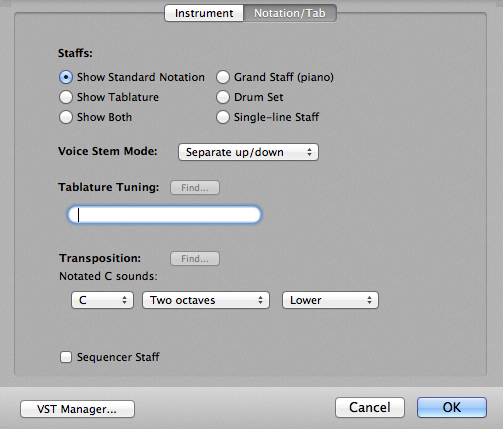

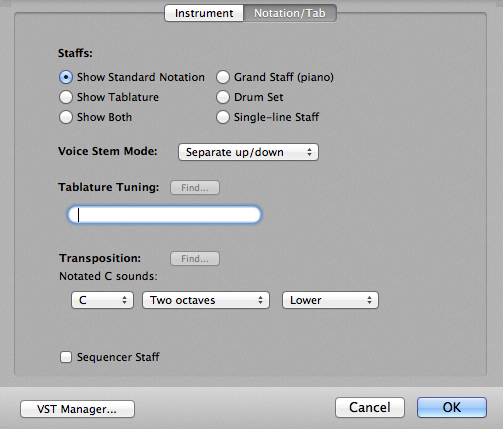

C1 to C9 on the Soprano Treble ClefAnd this is where one of the features of NOTION becomes very useful, where specifically you can define a soprano treble clef in such a way that the notes actually play one or two octaves lower or higher, with the practical strategy being to define staves for guitar, viola, and cello as playing one octave lower and to define staves for bass as playing two octaves lower, although this also can be handy for cello, since cellos has a bass range and a guitar style higher range . . .

In some respects, this strategy makes a bit more sense if you happen to play electric bass and electric guitar, because the lowest pitch four strings are the same, except for the octave, and there is a recording technique where an electric bass part is "doubled" on electric guitar to add clarity to the notes, where the electric guitar plays the same notes at the same locations on the fretboard as the electric bass but the notes on the electric guitar are an octave higher, all of which makes sense when you think about all the notes as being the same set of 12 notes but played in different octaves, where instead of needing to remember 88 notes, you just need to remember 12 notes and approximately 8 octaves, which I think is vastly easier to do conceptually . . .

As an example, this is the way I define the soprano treble staff for an electric bass, where the key is to observe that the notes are played two octaves lower . . .

Soprano Treble Staff Transposition for Electric Bass

Soprano Treble Staff Transposition for Electric Bass Another thing which is very handy is Nashville Notation, which is a shorthand strategy for chord patterns and is based on numbers . . .

Nashville Notation (wikipedia)And the reality for most

Country Western,

Rock and Roll, and

Rhythm and Blues, as well as

DISCO and

Pop genres is that by the time you learn 50 or so songs, for all practical purposes you know all the songs, since there are not so many chord patterns for songs in these genres, where there really are just two patterns based on two songs "Louie Louie" (The Kingsmen) and "Sleepwalk" (Johnny & Santo), where the "Louie Louie" pattern is "1,4, 5" and the "Sleepwalk" pattern is "1, -3m, 4, 5", with "-3m" being the relative minor third, where another way of writing the "Sleepwalk" pattern is "1, 6, 4, 5" . . .

Learning the electric bass parts for the songs on "Meet The Beatles", "The Beatles Second Album", and "Something New" works nicely for learning the basic numerical patterns for nearly every song in the aforementioned genres . . .

Studying songs written and performed by Hank Williams is another excellent strategy, as is learning a few Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly songs . . .

ConnieR wrote:Would it be best to do the instrumetnal parts in notion, then export it to another program to add a drum track?

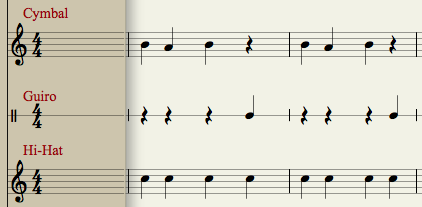

Drums and Latin percussion are instruments, and you certainly can write drumkit and Latin percussion instrument parts in music notation in NOTION, where the key is to learn how to do syncopation via music notation . . .

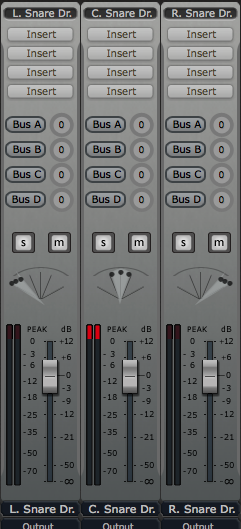

On the other hand, there are "drum machines" in Reason 6.5 (Propellerhead Software), and you can use the Reason 6.5 drum machines to play drums, which you can control via music notation in NOTION 4 on External MIDI staves . . .

No matter how you do it, everything needs to be coordinated and synchronized, and when there are verses, choruses, bridges, and interludes, there is no single pattern that covers everything, hence from my perspective it is easier to do it with music notation most of the time, although there are some interesting rhythms that can be generated automatically with Reason 6.5 drum machines . . .

~ ~ ~ continued in the next post ~ ~ ~