GaryExo wrote:Thanks.

As a matter of interest could you say what those things are which Notion disallows without explanation? I think that would be helpful to her.

Glad to help!

Most of these things that NOTION disallows without explanation are intuitive, where an example might be trying to add a staccato articulation to a rest, which of course does not work, because it makes no sense . . .

Another example would be selecting a whole rest and then trying to transpose it a fifth or perhaps an octave higher, which also makes no sense . . .

Some of these types of things travel with visual cues provided by the mouse pointer, where when something is allowed the mouse pointer is the correct shape or style, but when something is not allowed the mouse pointer might be different or if it is not different then clicking at the particular location does not do anything . . .

These are a few examples that come to mind, but as intriguing as it might be to have a list of things that make no sense, I do not have one, although the idea is intriguing . . .

GaryExo wrote:On another note, I don't think I would advocate ignoring all the other clefs as you say you do or writing everything in the same key or timing. I think she would be best to follow "proper" methodology.

My views on keeping everything in music notation as simple as possible are a bit non-standard, but being non-standard does not map arbitrarily to making no sense . . .

Mostly, I think it depends on the knowledge level of the person, where for example when someone is just beginning I think that simple assignments are better, as is everything when it is kept simple . . .

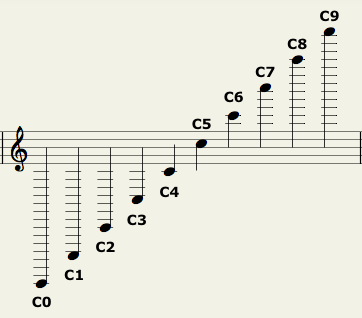

Consider someone who does not know the names of notes . . . One strategy is to start with 12 notes (C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B} and if possible to use the keys on grand piano to show the pattern for each octave and to distinguish the notes by an octave number using scientific pitch notation, where "Middle C" is C4 . . .

In other words, there are 88 keys, but there also are 7 repeating patterns of 12 notes and the patterns occur in octaves, where you can show the person "Low C", "Middle C", and "High C" while explaining that all of them a C but differ in octave . . .

The other strategy is to provide the person with something like this:

{[B#|C|C♮|♭♭D], [##B|C#|D♭], [##C|D|D♮|♭♭E], [|E♭|D#|♭♭F], [##D|E|E♮|F♭], [E#|F|F♮|♭♭G], [##E|F#|G♭], [##F|G|G♮|♭♭A], [G#|A♭], [##G|A|A♮|♭♭B], [A#|B♭|♭♭C], [##A|B|B♮|C♭]}

The second strategy is cruel, and it becomes egregiously cruel when it is introduced gradually over time, because what happens is that at each step along the way when the person believes that her understanding finally is clear, you introduce yet another exception, and in fact I think it is mean to do this . . .

In other words, consider that the person understands that ##C, D, and ♭♭E are names for the same note, and they are happy, confident with their knowledge, and generally feeling good about their progress in learning music . . .

What happens inevitably is that someone says, "Ah hah! But you forgot the natural, which is typical for slower students like you who never take the time to learn all the rules, all the wonderful maze of completely frivolous and pointless rules. You thought you were right, but you are wrong, and I am right. You lose, I win! Don't you love music!" . . .

Some of the naming stuff makes a bit of sense, where one of the goals for having sharps and flats is to avoid using a letter more than one time in a scale, where instead of having C followed by C#, the rule is to have C followed by D♭, and there is a bit of merit to having a distinct indicator for "a single half-step below" (flat) and "a single half-step above" (sharp), but this only works in a practical way for the notes on a piano that have adjacent black keys, although F♭ is a commonly used name for a note even though the note actually is E . . .

And the problem with having key signatures is that you cannot look at notes on the staff and know what they are without knowing the key signature and remembering which notes are flat or sharp, where for example the note on the staff might look like A4 when the key signature is C, but if the key signature is different then instead of being A4 it is either flat or sharp, depending on the specific key signature, with the result that you cannot look at music notation and immediately make sense of it without looking at other stuff and remembering a virtual festival of asinine rules . . .

When you learn the treble clef, along comes the bass clef and the notes are a whole step lower, or along comes the tenor clef, and so forth and so on, and something which truly is simple becomes a maze of complexity that only a career bureaucrat could love . . .

In fact, it tends to encourage the wrong type of people but to discourage the right type of people . . .

Explained another way, it is the music notation equivalent of a homeowner's community association that has rules regarding the acceptable height range and type of lawn grass; allowed colors and styles for mailboxes; and so forth and so on . . .

I fully understand the logic, and for some people it makes excellent sense and is a prudent way to introduce order into their lives, but this is not the case for everyone, and I tend to favor the strategy of keeping everything simple at first and to introduce the strange stuff later . . .

There are reasons for having different key signatures, different tempos, a variety of names for the same note, and so forth and so on, but I suggest that none of the reasons are mathematically elegant, which is the basic problem, and is one the things I like about electric guitar when all the chords are Barre chords, which also applies to electric bass, because once I know a song in the key of A, if I need to play it in the key of B, all I have to do is move everything upward by two frets, and the pattern is exactly the same so long as everything is within a general region or whatever . . .

And on a related note,

intervals are vastly important, and I think that learning intervals is a much better use of time than learning a festival of names for the same note . . .

It also depends on what the overall goal happens to be, where possible goals are (a) composing, (b) playing or singing an part composed by someone else, and (c) improvising, which actually is (a) but done in real-time on the fly . . .

If the overall goals are (a) and (c), which includes the "by yourself" variation of (b), then learning

intervals is the important focus, where learning intervals essentially maps to learning how to "play by ear", which is fabulous . . .

Fabulous!